By Matt Skoufalos

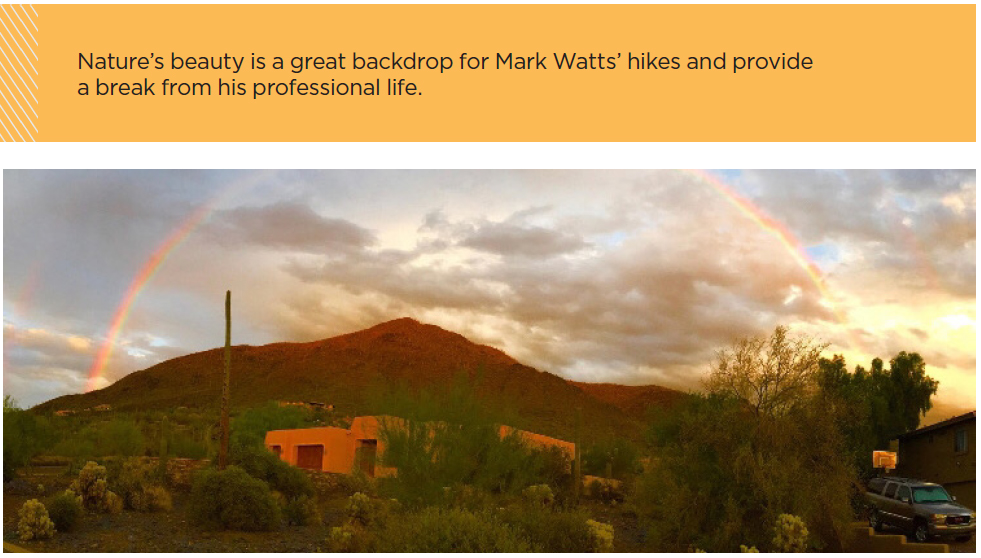

When Mark Watts, a native of Portland, Oregon, first moved to Arizona, he was struck by its natural beauty. Arizona has a rich history of commercial mining, and Watts was taken by the romantic notions of land claims laws related to its prospecting past.

Since the 18th century, people from Spain, Mexico, and the United States all have delved deep into the state’s mineral deposits, both formally and informally, seeking precious metals like gold, silver, and copper, and maneuvering themselves into opportunities to acquire the land beneath which these treasures are buried.

“The mountain-building episodes that brought mineralization to Arizona occurred mainly during the Precambrian and the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras,” wrote geologist Jan Rasmusson. “Volcanic eruptions and intrusion of granitic rocks and minerals in the associated veins rose from the eastward-dipping oceanic plate that was being subducted under the northwestward-advancing North American continent.”

All that tectonic and volcanic activity yielded a wealth of resources that people have been working to recover ever since. According to TheDiggings.com, which tracks mining deposits across the world, there are 469,629 records of mining claims on Arizona public land managed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and the United States Geological Survey (USGS) has records of 7,761 mines constructed there.

The state is also home to more than 48,000 patents on public land, according to The Land Patents, which inventories individual and corporate homesteading, mining, ranching and logging rights on public land. Mineral rights on public lands can be obtained through the BLM, allowing for further exploration; the process of getting those rights to public lands is complex, but petitioners can often acquire it if they find something valuable there.

“It piqued my interest to whether you could actually find valuable resources and actually do it,” Watts said.

Scottsdale, Arizona, where Watts moved several years ago to pursue a career in radiology, was once a ranching community. The city’s economic growth was fueled by the rich mineral deposits beneath its surface. Its copper mines fueled the American war effort during the 1940s, and the businesses that extracted the metals also profited heavily from their labors. In the decades that followed, as mining technology improved, future generations came to prospect those sites and further repurpose them.

On a much smaller scale, Watts has the opportunity of doing something comparable: on daily sojourns into the virgin desert of nearby Saguaro National Park, which lies just a 15-minute hike from his home, his eyes are always peeled for flashes of color against the brown and green of the landscape.

“Some people like to go to the casinos,” Watts said. “They drop a coin in a machine, and hope for a return on their investment. I like to go for a walk. I hope for a return on my investment by keeping my eyes peeled and looking for something that most people wouldn’t look for and wouldn’t bring it back home.”

Watts’ “retirement account,” as he calls it, isn’t vaulted away in a bank, nor digitized on a server. It’s locked up in hundreds of pounds of what he believes to be raw turquoise suitable for cutting up into jewelry-quality gemstone. Turquoise can get its blue-green color from the copper deposits in the stones, and it’s almost exclusively available in Arizona. When Watts and his wife take their morning hikes into the hillside, they’re walking over paths trod by humans for generations. He always brings along water, a hammer, and a chisel, to see what treasure the desert holds that they might have overlooked. Sometimes it’s semiprecious stones in small amounts; other times, it’s petroglyphs – rock carvings that vary in age from several hundred years to several thousand.

“When you’re out walking, you can see that people have been out here walking a long time in these deserts, just like my wife and I were,” Watts said. “I don’t know that they were miners, but they enjoyed their time in the desert, and left their mark on it too.”

“The university has carbon-dated the rocks in that hill at over a billion years old,” he said. “I find it fun to go up there and see if I can find something valuable that somebody else overlooked.”

“It’s about finding something beautiful in its natural state, and bringing it back home,” Watts said. “We go out with water, and we come back with rocks in our backpacks.”

Some of Watts’ adventuring hasn’t always gone as smoothly as a simple excavation.

Once when he was out on a solo hike, he recalled discovering a rock as big as the palm of his hand, showing greenish blue. It began to rain, exposing more of the rock’s surface, and revealing it to be a much larger stone that he estimated at 50 to 60 pounds.

“I started to carry it back down the hill, and because it was raining, and because I was going downhill, I slipped, and the rock went up in the air,” Watts said. “I fell down onto my back; it came down and landed between my legs. I called my son, and said, ‘Can you come and help me? I can walk, but I really want you to bring this rock back home.’ ”

The next day, his thighs were black and blue where the rock had struck them. Watts keeps the rock in his backyard as a conversation piece.

“I thought to myself, ‘What does this say about my personality that I called him not because I was hurt, but because I wanted him to help me carry it down the hill?’ ” he said.

Such are the hazards of the amateur geologist, but at least Watts comes by it honestly. In his day-to-day work, Watts is a data miner, combing through mountains of medical imaging reports that were initially produced for diagnostic purposes, but which may yield subsequent value if refined.

“We have hundreds of thousands of studies that we’ve collected, and what have we done with that information?” Watts said. “We’re finding value stored.”

“I have been collecting rocks for a long time and not developing them into jewelry, and we’ve been collecting data and not turning it into something that’s valuable for imaging,” he said. “The realization of potential, that’s the thing.”